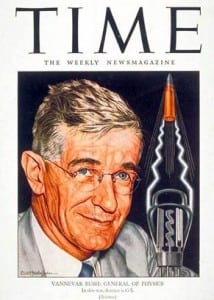

Many of us today are seeking ideas on how to deal with the massive, overwhelming deluge of data and information, both at work and at home. If that describes you, one recommendation I have is this: If you want a new idea, turn to history. One great icon of this info age, Vannevar Bush (1890-1974), may have insights that surprise and inform you. At a minimum you should find it inspirational that humans have always had great thinkers that can apply deep thought to big problems, and perhaps he will inspire you to create the solutions we need today.

Many of us today are seeking ideas on how to deal with the massive, overwhelming deluge of data and information, both at work and at home. If that describes you, one recommendation I have is this: If you want a new idea, turn to history. One great icon of this info age, Vannevar Bush (1890-1974), may have insights that surprise and inform you. At a minimum you should find it inspirational that humans have always had great thinkers that can apply deep thought to big problems, and perhaps he will inspire you to create the solutions we need today.

Vannevar Bush is a pioneer remembered for many things. He was an engineer, scientist and an educator of greats (including the great Claude Shannon). He is also credited with leading the response of science in support of national security prior to and during World War II. He was the President’s science advisor and head of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development during the war, and was a champion of the Manhattan Project.

One of his most famous essays was first published in The Atlantic in 1945. It is Titled “As We May Think.” The entire piece is worth a read because of its importance as a historical document. But it is also fascinating to read his visions for information storage and retrieval. He also articulated goals for the scientific community that are motivational even today, calling on the scientists who helped win that great war for national survival to turn their minds to advancing humanity. It is really an awesome piece.

A favorite quote from the article:

The world has arrived at an age of cheap complex devices of great reliability; and something is bound to come of it.

An introductory excerpt:

Of what lasting benefit has been man’s use of science and of the new instruments which his research brought into existence? First, they have increased his control of his material environment. They have improved his food, his clothing, his shelter; they have increased his security and released him partly from the bondage of bare existence. They have given him increased knowledge of his own biological processes so that he has had a progressive freedom from disease and an increased span of life. They are illuminating the interactions of his physiological and psychological functions, giving the promise of an improved mental health.

Science has provided the swiftest communication between individuals; it has provided a record of ideas and has enabled man to manipulate and to make extracts from that record so that knowledge evolves and endures throughout the life of a race rather than that of an individual.

There is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear. Yet specialization becomes increasingly necessary for progress, and the effort to bridge between disciplines is correspondingly superficial.

In a particularly prescient paragraph he articulates the need for better ways make use of information:

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

And he then did even more foreshadowing of the concept of “Big Data”, the coming deluge of massive amounts of information that humans cannot hope to analyze alone:

Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose. If the aggregate time spent in writing scholarly works and in reading them could be evaluated, the ratio between these amounts of time might well be startling. Those who conscientiously attempt to keep abreast of current thought, even in restricted fields, by close and continuous reading might well shy away from an examination calculated to show how much of the previous month’s efforts could be produced on call. Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

But there are signs of a change as new and powerful instrumentalities come into use. Photocells capable of seeing things in a physical sense, advanced photography which can record what is seen or even what is not, thermionic tubes capable of controlling potent forces under the guidance of less power than a mosquito uses to vibrate his wings, cathode ray tubes rendering visible an occurrence so brief that by comparison a microsecond is a long time, relay combinations which will carry out involved sequences of movements more reliably than any human operator and thousands of times as fast—there are plenty of mechanical aids with which to effect a transformation in scientific records.

He then goes on to outline needs that through today’s lens look like he is calling for smartphones, home computers and the Internet itself.

And he doesn’t stop there. He moves on to discuss the contributions that computing machines can make to analysis.

The repetitive processes of thought are not confined however, to matters of arithmetic and statistics. In fact, every time one combines and records facts in accordance with established logical processes, the creative aspect of thinking is concerned only with the selection of the data and the process to be employed and the manipulation thereafter is repetitive in nature and hence a fit matter to be relegated to the machine. Not so much has been done along these lines, beyond the bounds of arithmetic, as might be done, primarily because of the economics of the situation. The needs of business and the extensive market obviously waiting, assured the advent of mass-produced arithmetical machines just as soon as production methods were sufficiently advanced.

With machines for advanced analysis no such situation existed; for there was and is no extensive market; the users of advanced methods of manipulating data are a very small part of the population. There are, however, machines for solving differential equations—and functional and integral equations, for that matter. There are many special machines, such as the harmonic synthesizer which predicts the tides. There will be many more, appearing certainly first in the hands of the scientist and in small numbers.

If scientific reasoning were limited to the logical processes of arithmetic, we should not get far in our understanding of the physical world. One might as well attempt to grasp the game of poker entirely by the use of the mathematics of probability. The abacus, with its beads strung on parallel wires, led the Arabs to positional numeration and the concept of zero many centuries before the rest of the world; and it was a useful tool—so useful that it still exists.

For more you will want to check out The Atlantic. Good on them for keeping this essay alive for the future. Find it here.