The term “Big Data” has been around quite a while (see a short history of Big Data here), but really came into mainstream discussion in 2007 (which also happens to be the first year CTOvision used the word). The phrase had an important role in helping many of us think through new architectures for how to store and analyze data. Things were different from data storage and analysis of the past and the term helped us conceptualize some of that difference.

Part of what was different was the implications of privacy that many of us saw coming. Few were as prescient as Kord Davis, who ran a series here on the Ethics of Big Data (which was also the topic of a book he published in 2012 by the same title). Lots of us are thinking about Kord’s words of wisdom these days. Techies everywhere, especially data scientists, have also long been tracking the ideas of DJ Patil, the first US Chief Data Scientist, who has advocated that data scientists and executives and leaders of all types understand the ethical dimension of what we are doing. DJ captured many elegant thoughts on this topic in a widely read post on medium at “A Code of Ethics For Data Scientists.”

DJ and Kord are not alone. Many technologists, business leaders, politicians, academics informed citizens have been tracking these issues for years.

Then all of a sudden, surprise surprise surprise. On 17 March 2018, The Guardian reported that a political research and data science firm called Cambridge Analytica had inappropriately harvested data from the Facebook profiles of over 50 million of us who had not provided consent for their data to be used for political and psychological profiling.

In discussion with techies, as well as with my surveillance of the social media of many I admire, it seems few were really surprised that this sort of thing happened. Similar things seem to happen all the time, including data from Facebook being used for multiple political research efforts and campaigns over many years.

Some context from friends via Twitter:

https://twitter.com/mtanji/status/976576577571098624

I've read Zuckerberg's statement today; doesn't appear all that different from what he earnestly professed/promised last year, under pressure. The DNA of "hacking human privacy" still seems to run in his/FB's veins. Maybe worth remembering this from 2004: https://t.co/QTkQad4PIL

— Lewis Shepherd (@lewisshepherd) March 21, 2018

Facebook's defense that Cambridge Analytica harvesting of FB user data from millions is not technically a "breach" is a more profound & damning statement of what's wrong with Facebook's business model than a "breach".

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) March 17, 2018

The problem with Zuckerberg's post is this. In 2011, FB was caught deceiving people about how it violated their privacy. It signed an agreement w/the FTC pledging to stop doing that. Today, Zuckerberg is outlining the steps he promised to take in 2011.

— Matt Stoller (@matthewstoller) March 21, 2018

A point I would make for all of us who strive to learn the potential of technology: We should all take it as a duty to consider not just our own ethics, but how to inform others on the potential damage that can be done by data. This includes, unfortunately, the potential for damage when the data is being used in exactly the way it was designed to be used.

Another point: Humanity can fix this stuff. It will take collective action, which can and probably should include government regulation. But we can fix it.

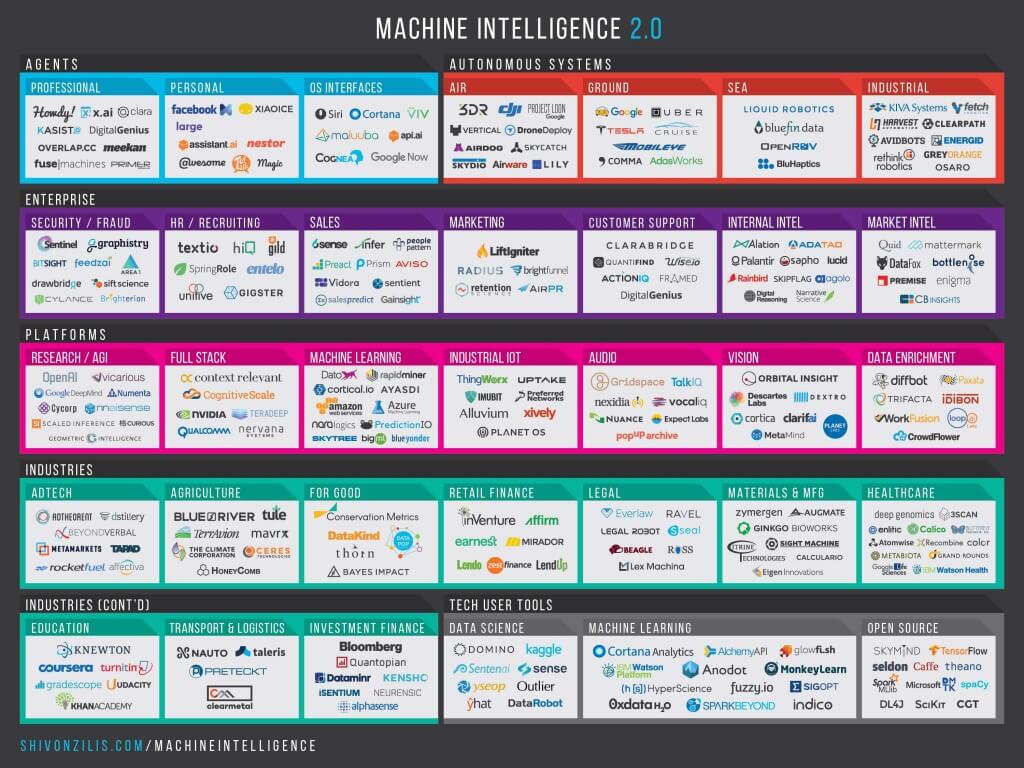

The field has had its ups and downs over the years, we have seen many "AI Winters" come and go. But things are different now. The use of AI is growing dramatically with the proliferation of high powered computers into homes and businesses and especially with the growing power of smartphones and other mobile devices.

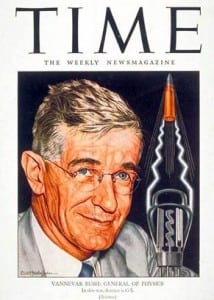

The field has had its ups and downs over the years, we have seen many "AI Winters" come and go. But things are different now. The use of AI is growing dramatically with the proliferation of high powered computers into homes and businesses and especially with the growing power of smartphones and other mobile devices. Many of us today are seeking ideas on how to deal with the massive, overwhelming deluge of data and information, both at work and at home. If that describes you, one recommendation I have is this: If you want a new idea, turn to history. One great icon of this info age, Vannevar Bush (1890-1974), may have insights that surprise and inform you. At a minimum you should find it inspirational that humans have always had great thinkers that can apply deep thought to big problems, and perhaps he will inspire you to create the solutions we need today.

Many of us today are seeking ideas on how to deal with the massive, overwhelming deluge of data and information, both at work and at home. If that describes you, one recommendation I have is this: If you want a new idea, turn to history. One great icon of this info age, Vannevar Bush (1890-1974), may have insights that surprise and inform you. At a minimum you should find it inspirational that humans have always had great thinkers that can apply deep thought to big problems, and perhaps he will inspire you to create the solutions we need today.

This post is a follow on to our report “

This post is a follow on to our report “